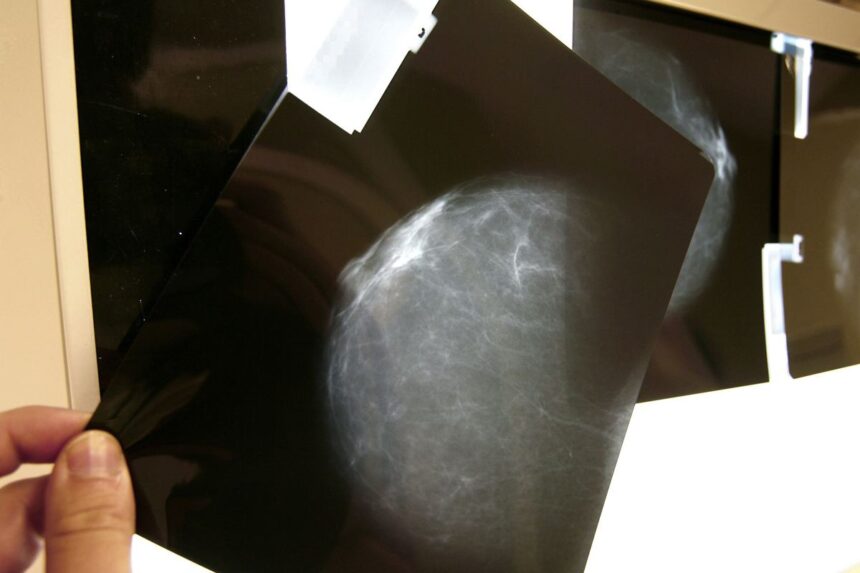

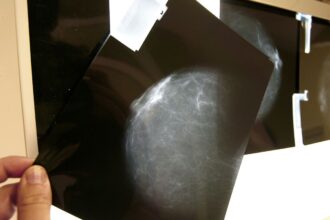

A preclinical study led by the Hospital del Mar Research Institute and the Vall d’Hebron Institut d’Oncologia in Barcelona (Spain) has discovered that senescent cells, those that stop dividing and accumulate in the body with age, have a decisive influence on the evolution of breast cancer.

The research, published this Friday in the journal Science Advances, has analyzed in animal models the role of these cells in the growth of tumors and the appearance of metastases.

Researchers have concluded that senescent cells, also known as “zombie cells,” can promote or slow the progression of breast cancer depending on how they are acted upon.

To this end, the researchers have developed a new transgenic mouse model, with DNA modified in laboratories, which makes it possible to study more precisely the interaction between senescent cells, the immune system and cancer cells during the early stages of the tumor.

The results of the study have shown that eliminating senescent cells at an early stage of tumor development can have a counterproductive effect on the patient, as it favors cancer proliferation and metastasis formation.

This consequence is produced by macrophages, large immune cells that guard the body to protect it but, in the absence of the “zombie” cells, join the tumor and contribute to its growth.

The process is explained by the fact that, as the senescent cells disappear, the macrophages start to promote tumor growth by producing the cytokine CCL2.

The cytokine CCL2 is a harmful molecule that, on the one hand, stimulates cancer cells to grow and multiply uncontrollably and, on the other hand, blocks the action of T lymphocytes, which are responsible for attacking and destroying the tumor.

Thus, the study shows that the immune system itself can end up protecting the tumor when senescent cells are eliminated without an adequate strategy.

Risks and new therapeutic avenues

Researcher Marta Lalinde Gutiérrez, from the Hospital del Mar Research Institute, has warned of the risk of applying anti-aging therapies based on the elimination of senescent cells without taking into account the oncological context.

However, the study also points to a promising potential therapeutic strategy, as the combination of eliminating senescent cells with inhibitors of the deleterious molecule CCL2 has been successful in reducing tumor size and eliminating metastases in animal models.

“The key is to act at the right time and combine both intentions,” said Lalinde, who stresses that this approach could be beneficial in the treatment of early stages of breast cancer.

The director of the Hospital del Mar Research Institute, Joaquín Arribas, has advanced that the team will now work to develop CCL2 inhibitors and validate the results in patient samples.

The research was funded by the “la Caixa” Foundation, the CIBER de Oncología, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and the World Cancer Research Fund.

With information from EFE